My age puts me smack dab in the middle of the woo-woo generation, when many people engaged in activities, or shared in belief systems, that were criticized as unscientific, spacey or just plain bizarre. For example, talking to your plants was purported to make them bigger, greener or more florid. This hypothesis generated a huge number of science fair projects, but no clear answers (so far as I know – but I admit that I have not done the appropriate research!). But, it turns out that plants do talk to each other and to some animals. When attacked by herbivores, many plant species will emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air that can have two effects. First, these VOCs can alert nearby plants that herbivores are in the area, and that they should start producing defense compounds in their tissues that will repel these herbivores. Second, these VOCs can alert predators that herbivores are present, and they should swing by and eat them.

Several studies have shown that female and male plants may differ in several ways that could affect communication. Females typically invest more in reproduction, grow more slowly and invest more in defense against herbivory. Xoaquin Moreira and his colleagues wondered if sexual dimorphism in defense investment would result in differences between males and female in how they talk to each other. They chose the woody shrub Baccharis salicifolia, in which females grow more slowly but invest more in chemical defense and thus are infested by fewer herbivores than are males. They focused their study on chemical responses of the plant to the highly-specialized aphid Uroleucon macolai, which only feeds on two Baccharis species.

Baccharis salicifolia hosting an army of herbivorous aphids. Credit: X. Moreira.

The researchers used greenhouse experiments to explore how Baccharis uses VOCs for communication. To control aphid movement, each treatment was done in a mesh cage, with one centrally located VOC emitter plant (of either sex), and one female and one male receiver plant equally distant from the central plant. Control emitter plants were untreated, while herbivore-induced emitter plants were given 15 mature aphids, which fed and reproduced on the plants for 15 days. After 15 days Moreira and his colleagues removed all of the emitter plants and all of the aphids, and then inoculated each receiver plant with two adult aphids. The researchers measured aphid reproductive rate on the fifth day as their measure of aphid performance, or of plant resistance to aphids.

Emitter Baccharis salicifolia plant flanked by one male and one female receiver plant. Credit X. Moreira.

Aphids did much more poorly on male and female receiver plants that were associated with male herbivore-induced emitter plants (top graph below). This implies that these receiver plants became resistant to aphids as a result of their exposure to an airborne substance released by the male emitter plant. When the researchers used female emitter plants they found something very different. There was no effect on male receivers, but still a very strong effect on female receivers, which had a much lower aphid reproductive rate than the female plants exposed to untreated female emitter plants (bottom graph below).

Reproductive performance of aphids raised on control receiver plants (emitter plant with no aphids – clear bars) and herbivore-induced emitter plants (gray bars). Two left bars show performance on male receiver plants, while two right bars show performance on female receiver plants. Top graph shows data for male emitters and bottom graph shows data for female emitters. Error bars = 1 SE. *** indicates P < 0.001.

Showing differences between sexes in communication is important, but the next step is to figure out how this happens. In previous research, Moreira and his colleagues identified seven different VOCs that Baccharis emitted after aphid herbivory. So they explored whether there were differences between males and females in how much of each VOC they emitted in response to aphids. As before, they subjected some plants (of each sex) to herbivory and others were untreated controls. They then bagged each plant, and passed the collected vapors over a charcoal filter trap at a constant rate for an equal period of time. After extracting the substances from the charcoal, the researchers used a gas chromatograph to identify and quantify the VOCs.

Setup for collecting VOCs from Baccharis salicifolia. Credit X. Moreira.

The most impressive finding was a fivefold increase in pinocarvone release by female herbivore-induced plants in comparison to controls. In contrast, in males there was only a minor pinocarvone effect.

Relative increase in VOC emission following aphid attack in female (clear triangle) vs. male (filled triangle) Baccharis salicifolia. The induction effect is the log response ration (LRR) which is the natural log of (emission by the herbivore induced plants divided by the emission by the control plants). Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

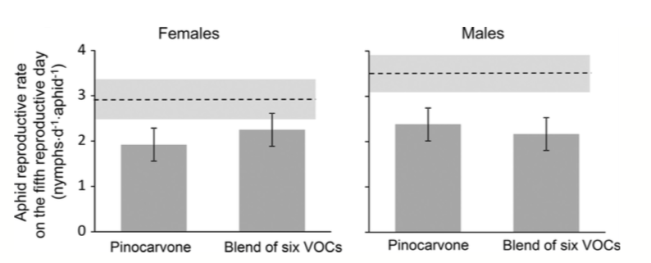

Having discovered that females emit much more pinocarvone than males, the next question was whether females are more sensitive to pinocarvone, or in fact to any of the other VOCs. So Moreira and his colleagues exposed plants to one of three treatments: 100 ul of pure pinocarvone, 100 ul of six VOCs including pinocarvone, and a control (no VOCs). They discovered that all experimental treatments reduced herbivory in comparison to the controls, but that there was no difference between males and females in how they responded.

Reproductive performance of aphids raised on female plants (left graph) or male plants (right graph) subjected to pinocarvone or a blend of six VOCs (including pinocarvone) in comparison to reproductive performance on untreated control plants (dashed line on top of each graph). Shading surrounding dashed line indicates 1 SE. Error bars are 1 SE.

This lack of different response between male and female plants to pinocarvone was a bit surprising; the researchers speculate that both males and females have pinocarvone receptors, but that female receptors are more sensitive (or numerous). If true, natural emissions of pinocarvone may suffice to induce a response in female but not male plants. But the artificial emitters may have released enough pinocarvone to stimulate male plants to respond as well. Clearly there is much more work to do here.

The researchers also wanted to know whether plants were more sensitive to VOCs produced by genetically identical plants (clones) in comparison to genetically-distant plants. They discovered no influence of genetic relatedness on plant response to herbivory. This is important, because from an evolutionary standpoint, there is no obvious reason why a plant would want to warn an unrelated plant that it was about to get eaten. An adaptive explanation is that relatives may tend to live near each other, so an emitter plant still benefits indirectly by promoting the survival of relatives who carry a proportion of genes identical to its own genetic constitution. One possible non-adaptive explanation is that a plant may use VOCs as a way of quickly communicating with itself, informing distant tissues that they need to produce defense compounds. Nearby plants may simply be eavesdropping on this conversation, and using it to their advantage.

note: the paper that describes this research is from the journal Ecology. The reference is Moreira, X., Nell, C. S., Meza‐Lopez, M. M., Rasmann, S. and Mooney, K. A. (2018), Specificity of plant–plant communication for Baccharis salicifolia sexes but not genotypes. Ecology, 99: 2731-2739. doi:10.1002/ecy.2534. Thanks to the Ecological Society of America for allowing me to use figures from the paper. Copyright © 2018 by the Ecological Society of America. All rights reserved.