North American forests are being invaded. The invading forces use chemical warfare to attack the native inhabitants and to repel counterattacks by hostile enemies. As it turns out, the invader is the humble garlic mustard, Alliaria petiolata, which releases toxic chemical compounds into the soil that reduce the growth rate of many native plant species, and has strong chemical defenses that makes it unpalatable to most herbivores.

Garlic mustard invasion. Credit Pam Henderson

Lauren Smith-Ramesh wondered why garlic mustard was not even more successful as an invader. Its chemical arsenal should allow it to overrun an area, but she (and many other researchers before her) observed that garlic mustard invasions often decline after a while. As part of her investigations into garlic mustard’s use of chemicals to inhibit native plants, Smith-Ramesh collected seeds from plants from different populations. While shaking these seeds into bags, she noticed that web-building spiders often colonized the garlic mustard’s seed-bearing structure (silique). Were these spiders somehow behind the garlic mustard’s surprising lack-of-success?

Garlic musard silique with web. Credit Lauren Smith-Ramesh

Spiders can benefit plants in several ways. As important predators in food webs, spiders can kill large numbers of herbivorous insects that might otherwise attack a plant. In addition the decaying corpses of their insect prey can add vital nutrients to soils. Garlic mustard does not enjoy these potential spider-associated benefits, because spiders colonize the garlic mustard after it has already gone into decline, and also because garlic mustard is already well-protected (chemically) against herbivorous insects.

About 60% of the spiders were this species – Theriodiosoma gemmosum. Credit Tom Murray.

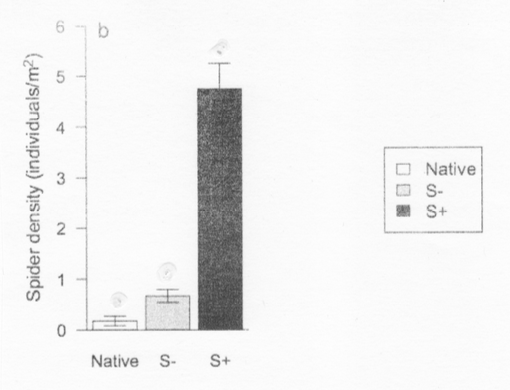

Smith-Ramesh first wanted to understand the relationship between seed structures (siliques) and spider abundance. She established three different types of plots that measured 2 X 2 meters: (1) S+, which had mustards with intact siliques, (2) S-, which had mustards with siliques removed, and (3) N, which had no garlic mustard plants at all in 2015. After several months, she collected all spiders from the middle square meter of each plot. Plots with garlic mustard with intact siliques (S+) had, by far, the highest spider density. S- plots had a somewhat higher spider density than N plots, which Smith-Ramesh attributes to spiders wandering in from just outside the S- plots (which tended to have more silique-bearing garlic mustard plants nearby than did the N plots). Based on this experiment Smith-Ramesh concluded that garlic mustard siliques were dramatically increasing spider density.

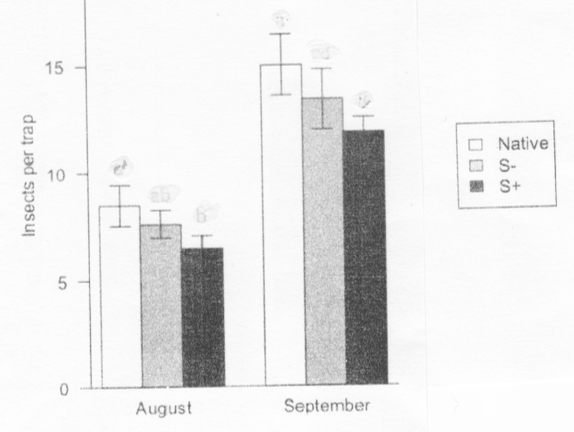

But did increased spider density in S+ plots reduce the number of herbivorous insects, thereby benefiting nearby native plants? Smith-Ramesh set up insect traps that collected insects over two 48 hour time periods – once in August and again in September – in each of the S+, S- and N plots. Both surveys showed fewest herbivorous insects in the S+ plots. This supports Smith-Ramesh’s hypothesis that native plants are benefitting from higher spider density associated with garlic mustard siliques.

Next, Smith-Ramesh wanted to know whether the decrease in herbivorous insects benefitted native plant growth. To test this directly, she transplanted three types of native plants into her S+, S- and N plots. One of the species, the Hairy Wood Mint Blephilia hirsuta, enjoyed a 50% biomass boost in S+ plots compared to S- plots. The other two native plants species showed very little effect.

Smith-Ramesh collecting data with three siliques in the foreground. Credit: Lauren Smith-Ramesh.

Garlic mustard plants with intact siliques also benefitted the soils by increasing the amount of available phosphorus by approximately 60%. This phosphorus may have originated with insect carcasses that made their way into the soil and released their nutrients. In theory, soils with higher phosphorus availability could help support the growth of native plants. Smith-Ramesh plans to explore other plant communities that are suffering from different invasive plants, to see whether these invaders are also inadvertently providing resources or conditions that may undermine the success of their invasion.

Nice short and simple for my limited attention and brain!

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

I aim to please!

LikeLike

I’ll share this example in my science class – nice little tale of interactions in the woods. Is there a specific term to describe the relationships?

LikeLike

Interesting question about a term to describe the relationships, in that I don’t have a good answer. When one organism (or species) influences the survival/reproductive success of a second organism (or species) via its influence on a third, we call this an indirect effect. So the garlic mustard benefits native plants by facilitating spiders. This is then indirect facilitation of native plants. But the kicker is that the native plants can then more successfully compete with the garlic mustard, which puts another link in the web, with the added complication that this final link has the effect of causing garlic mustard to have a negative effect on its own (or its offspring) survival/reproductive success.

Maybe put your students to work looking for other such examples!

LikeLike